Modeling Business Processes and Domains

New Chapter in Part 3 of MMA, Book 1

Here’s the latest draft chapter in MMA Book 1, covering the modeling of business processes and domains. This is yet another topic that receives light coverage in data modeling literature, and is too important to ignore. There are certainly lots of opinions on how to model business processes and domains, and I’m certain to have missed someone’s favorite pet methodology or approach. Apologies in advance. This is what’s worked for me, and you might have different experiences. Would love your feedback on what’s written (drop it in the comments).

I’m guessing this is Chapter 13, but might re-order the sequence as I begin editing the book. This is also the final “big” chapter in MMA Book 1. There will be a few smaller chapters I’ll drop here, but I’m finally on to editing the book! That’s a great milestone, so thanks for your support.

Thanks,

Joe1

In 2024, a major airline, let’s call them “Hellta,” bet the farm on a massive migration to a new, state-of-the-art data platform. The system to be replaced, a tangled web of legacy mainframes, was clunky, held together with duct tape, and always on the verge of failing. The latest technology promised salvation: faster, cheaper, and more scalable. The data team, full of brilliant software and data engineers, spent nearly two years laser-focused on the technical details: optimizing the new lakehouse schemas, writing complex ETL/ELT and streaming pipelines, and ensuring the various systems could connect and scale.

Technically speaking, they succeeded brilliantly. The launch was a disaster. Although the new data platform worked as designed, the numbers it produced didn’t make sense. Teams, depending on the data, were, umm, flying blind. The business’s trust in the engineering team evaporated almost overnight.

The Hellta Flight Operations team insisted that an “On-Time Arrival” was based on wheels-down time. The Customer Compensation team, however, defined it as the moment the gate door opened, a difference of several critical minutes. Finance defined a “customer” as an entity with a billable account, while Marketing defined a “customer” as anyone who had ever visited the booking page. Not that the engineers designing the system took the time to ask.

The impacts of not asking were tangible and embarrassing. Customer Compensation calculated $42 million owed to passengers for Q3 delays. Finance reported $18 million in delay liability. Accounts Payable actually disbursed $29 million. Somewhere, $24 million (the difference between what Finance and Customer Compensation calculated) either went out the door that shouldn’t have, or passengers who deserved compensation never got it. Meanwhile, Marketing’s “customer count” of 2.3 million looked great in the quarterly deck, until someone noticed it included 800,000 people who had never purchased a ticket. Big oops.

The engineers had perfectly modeled the systems. They created perfectly partitioned lakehouse tables and “data models” that worked flawlessly within the performance constraints of the new data system. But they failed to model the business’s messy interconnected processes and capture the vocabulary across various domains of meaning, spread across different teams. The engineering team was fired.

We Model the Business, Not Just Data Systems

“The map is not the territory” - Alfred Korzybski.

Too many data practitioners think of data modeling solely in terms of system implementation. They focus on database schemas, data pipelines, or how datasets join. While these technical details are necessary to get work done, obsessing over them before a proper data model is in place is backwards. The model comes first, and the systems that serve it come last.

Underneath the data’s structure lies the reality the model is trying to represent. When we model data, we must first understand what we are modeling. This chapter ties together the building blocks you’ve learned so far, helping you to “learn how to see” the processes and domains that crisscross every organization.

Business Processes and Domains Explained

The terms business process and domain are ubiquitous in technology and data modeling, yet often overloaded. Let’s clarify exactly what they mean in the context of Mixed Model Arts.

A business process is a sequence of actions performed by specific actors (people, systems, agents, or machines) that transforms inputs into outputs to achieve a business outcome. This sequence is fundamentally about horizontal flow: an event is triggered, ordered steps are taken, something changes, and a result is achieved. We will use the terms business process and process interchangeably.

You encounter processes every day: applying for a loan, ordering online, getting a driver’s license, or buying groceries. Sometimes processes are clearly documented; other times, they are understood and followed implicitly. But regardless of documentation or consistency, a process describes how work actually gets done.

A domain is a boundary of meaning, often a specific area of an organization where language, rules, data, and responsibilities are consistent and coherent. Unlike processes, domains are not about horizontal flow. Instead, a process might encompass several domains. Sometimes a domain is macro, like a major department (Sales, Operations, Marketing). Other times, a domain forms at a specific functional level, called a subdomain (Inventory, Order Fulfillment, Compliance).

In data modeling terms, a business process is where events originate, and data is created or changed. A domain is where meaning lives and is protected.

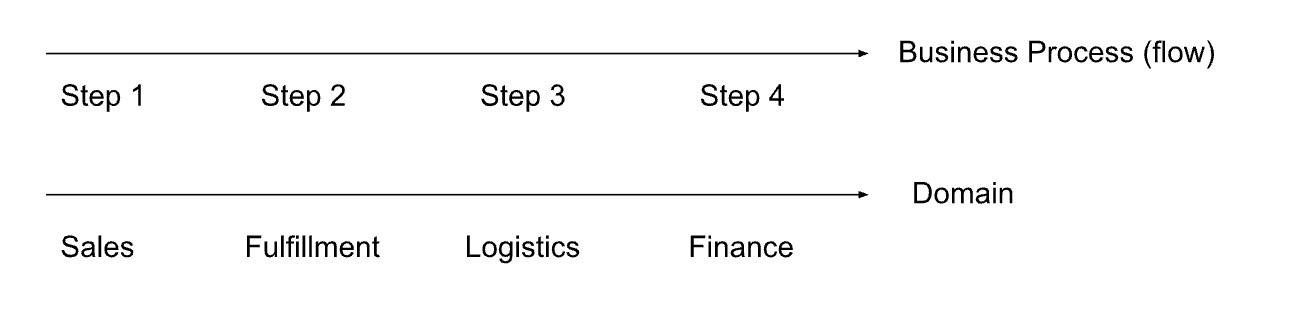

Business processes naturally intersect multiple domains. In Figure x-y below, we see a generic business process flowing through the Sales, Fulfillment, Logistics, and Finance domains.

Figure x-y: How business processes and domains relate to each other.

You might wonder if the process or domain comes first. It is a chicken-and-egg scenario. Sometimes processes dictate the domain; sometimes domains constrain the process. In reality, they co-exist and co-evolve. But for the data modeler, the order of creation doesn’t matter as much as the method of discovery. It depends on what you’re modeling. If you’re creating a data model for a data warehouse, you’re integrating data from multiple domains. Here, I find it’s easiest to start with understanding a business process. Domains are easiest to discover after analyzing the business process. As you trace the flow of work through a process, the domain boundaries naturally appear at points where meaning, rules, ownership, or actors change. In other cases, such as modeling a microservice, your modeling scope will be narrower, focusing on a domain or subdomain.

A common question is, why not jump straight to implementing the data model in your data system? If you want to be like Hellta’s engineering team, go for it. But hopefully the story illustrates why jumping straight to physical implementation isn’t a wise approach. It’s better to understand what you’re modeling, so let’s look at why we should first understand the processes and domains we’re modeling.

Why Model Processes and Domains?

In the last section, we dove into the gory details of the modeling building blocks. We discussed instances, identity, attributes, relationships, time, events, grain, and counting. But on their own, these building blocks are helpful but incomplete. They are like having a pile of high-quality bricks and 2x4s without a plan for how they come together. Do you build a house, a shed, a skateboard, or a wooden car? Sadly, I’ve seen far too many shoddy data models built by haphazardly nailing randomly cut 2x4s and stacking bricks on top of each other without a plan. The result is what you expect. And I suppose to extend the analogy to a more ridiculous degree, you could try to build a data model that encompasses every idea, workflow, and anything else in the universe. But that’s neither feasible nor practical.

Obviously, we need a balanced way to constrain what we’re modeling. These constraints are boundaries. To build something that brings shared meaning to both humans and machines, we need to intentionally assemble these blocks within a boundary. Business processes and domains provide the necessary boundaries for a data model, defining its scope and context. Processes represent the workflow’s scope (e.g., “We are only modeling the ‘Checkout’ flow, not the ‘Return’ flow”). Domains provide the boundary of language (e.g., “What does ‘customer’ mean here?”). Together, processes and their domains convey a shared understanding of who or what consumes the data model.

Our data models in the era of Mixed Model Arts must serve three distinct personas, sometimes collectively and other times separately. When defining the model’s boundaries, it is essential to remember who or what we are modeling. Each audience requires the boundaries of processes and domains to be communicated in different ways.

People are visual thinkers. Flowcharts, diagrams, and whiteboards allow people to “see” the business process and validate if the model matches reality. Processes might also be documented, combining words, tables, and visualizations. For humans, the model is a map that helps them navigate the nuances of a process and how it operates across domains.

Applications and data systems need structure. Traditional applications (ERP, CRM, or custom web and mobile apps) are the engines that drive business processes. They don’t care about the visual map or the nuance of diagrams. But they do need a precise data model to ensure data integrity and performance. In applications and data systems, the data model dictates exactly how to store and retrieve the process’s state.

Machines such as AI agents need semantics. As I write this, this is the new frontier. Unlike applications and data systems, which follow rigid rules, AI agents (namely LLMs) benefit from context. Right now, this is provided through a combination of documentation, metadata, structured data from applications and data systems, and additional semantic context that ties all of this data together (such as semantic layers, ontologies, and knowledge graphs) to understand the task it needs to complete, often working alongside other agents to fulfill an overall process. For AI, this collection of structured and contextual data provides the context needed to make decisions or answer questions.

Historically, we treated these as separate disciplines. Business analysts created visual dashboards and reports for human decision-making, and software and database engineers built the applications and data systems. AI wasn’t in the picture, except as bespoke ML models deployed for specific tasks. Documentation was usually ignored or left in outdated wikis that nobody read. This was the classic silo trap, and I wager it’s responsible for many of the problems that led organizations to fail to get value from technology initiatives. AI is changing this, and the possibilities for data modeling are just now being discovered, as we’ll explore through this book series. To model effectively, we must unify these silos. A change in the business process must be reflected everywhere humans and machines consume data, evolving as things change.

As organizations grow, so does entropy. Simple processes become complex, leading to communication breakdowns and poor team coordination. While small-scale processes can be managed informally or verbally, this approach quickly fails as the organization scales. For large organizations, a map is essential.

These modeling concepts align with Domain-Driven Design (DDD), a software engineering approach popularized by Eric Evans in the early 2000s. DDD zooms in on the different ways an organization does its work. An organization might have functions in Sales, Marketing, and Finance, each dedicated to fulfilling its own objectives within the broader organization. These functions have different goals and contexts. DDD advocates modeling these functions around a “bounded context.” In the data world, similar ideas have surfaced through trends like Data Mesh, created by my good friend, Zhamak Dehghani. The core philosophy remains the same: it’s impossible to model the world as a whole at once. Sometimes, it’s easier to break things into their constituent parts.

Complexity must be made manageable, governable, and understandable by breaking it down into domains and processes. Whether you call it DDD, Data Mesh, or just specific common sense, the goal remains the same. You cannot model the whole world at once. But if you respect the process’s boundaries and the domain’s meaning, you can finally build a model that better reflects reality.

How to “See” a Business Process

For most data modelers, an organization’s processes already exist. We need to “see” the process and map it to a data model. Our role is not to redesign or optimize the process, no matter how inefficient or irrational it may appear. Our data model might inform the process owner about ways to improve their process. And there will always be a temptation to “fix” a bad process, but that work belongs to the process owner(s) and leadership teams. The process is what it is.

Capture the Process Flow

“Model utility depends not on whether its driving scenarios are realistic (since no one can know for sure), but on whether it responds with a realistic pattern of behavior.” - Donella Meadows, Thinking in Systems.

Some people say a data model should exactly mirror reality. This is unrealistic. We can try to approximate reality as closely as possible, but we’ll never truly capture everything. A model is a model. A better way to model a process is to capture its structure, flows, and how it responds to changes over time.

The initial objective in modeling a business process is to capture the workflow’s structure and flow. This phase focuses solely on the process’s motion, intentionally setting aside its deeper business meaning for the moment. Simply put, where does the process begin and end, and what happens in between, and by whom (or what)? Establishing these clear boundaries is essential to accurately capture the broad coverage of a process while preventing accidental scope creep, such as unintentionally modeling an entire company or IT system, or allowing the domain to sprawl beyond its necessary focus.

Business process mapping typically visualizes the workflows that generate and evolve data. In formal circles, this is often done using the BPMN (Business Process Model and Notation) standard. However, we will focus here on the high-level concepts and flow, rather than the nuances of strict graphical notation.

Business process mapping is a demanding job, sometimes in ways you won’t expect. We must discover the process as it actually works today, warts and all, not how management thinks it works. To make this work repeatable, here is a relatively straightforward method that’s worked for me to understand nearly any business process. Of course, your mileage will vary depending on the process you’re mapping and how you’re gathering your information. Here’s how this ideally works.

First, identify the boundaries of a process’s start and end. Within these boundaries, the next step is to identify the key components that give the process its coherence and momentum. Every process must have a definitive moment when it begins, which is the triggering event, which could be an action, request, or specific condition that initiates the event.

Equally important is the business object in motion, the central “thing” that is being acted upon and fundamentally changed as the process unfolds. This could be a tangible item, such as a shipment, or a record, such as a customer profile, or an administrative entity, such as an order, claim, ticket, or request. Most business processes serve one purpose: to transition a core object from one state to the next.

We must also identify the actors involved: the humans, automated systems, AI agents, or other components responsible for executing the work. Different actors come with different implications regarding their responsibilities, inherent constraints, and levels of authority within the process.

Sometimes this isn’t 100% predictable. Humans and AI agents might vary in how a process is executed. Humans are expected to follow rules, but we’ve all seen cases where humans also bend rules. For AI agents, their non-deterministic nature can introduce unexpected behavior. Unlike a software script that always executes step B after step A, an AI agent might decide to skip step B if the prompt context is ambiguous or the model drifts. For some reason, the agent might skip to step C. When modeling a process involving agents, your data model cannot just record what happened. The model must also record the input context (prompts, available tools, model version, etc.) that led to it. Otherwise, you cannot debug the process when the agent inevitably goes off in some weird direction.

Finally, we map the sequence of steps: what actions occur, in what order, and what conditions govern the path between them. It is crucial at this stage to avoid over-formalization. The goal is to discover a process’s coherent and logical flow.

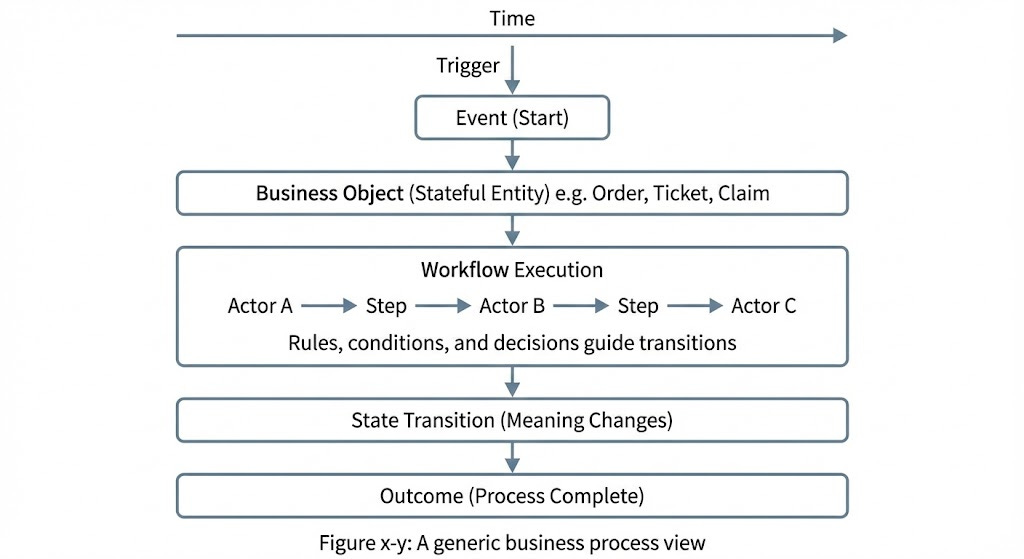

Taken together, these components form a powerful, simple pattern that defines the process as a flow through time, not merely a collection of disconnected tasks. This holistic view is expressed as a defined event that triggers a workflow, which mobilizes various actors to perform necessary actions, leading to a change in the state of the central business object and ultimately producing the process’s required outcome.

Here’s a generic look at these process steps, called a process view.

Figure x-y: A generic business process view